Vishnu Makhijani -

It has withstood the ravages of time but is now on its last legs.

But while “no effort should be spared to arrest the corrosion and to protect what remains as long as technology can combat the issues”, the “inevitability has prompted many art lovers to contemplate the building of a new Sun temple in the archaeological and spiritual tradition of Konark”, says Anil Dey, an engineer by profession who has spent six decades studying the temples of Odisha, in this seminal work.

“The matter is being raised in the media for two decades,” Dey writes, adding that after he voiced the “dream” through a small column in March 2006, many others supported the idea.

Former legislator Bikram Keshari Barma had raised the issue at the Odisha Sanskruti Mancha in 2009, saying that Rs 1,000 crore ($150 million) had been sent to the government. ‘‘No details were given and nothing was heard about the proposal later,” Dey writes.

The topic surfaced again in a meeting of the Konark Surakshya Samiti, a local group in Konark, in November 2010. ‘‘The then Chief Secretary of Odisha had opined that a small model could be tried.

Small or big, the reaction indicated that the government was not opposed to the proposal.

There were no follow-ups and the matter remained a dream.”

Three years later, Dey writes, the matter was once again raised by Sri Raghunath Mohapatra, a sculptor and Padma Vibhushan awardee.

The details of his proposal “are not known but from what appeared in the media, it seems Mohapatra wanted to give shape to an artist’s perception of Konark drawn by a British artist at the instance of Andrew Fergusson in the 19th century”. This time, however, the Tourism Minister paid heed and a meeting was held at the level of the Chief Secretary in February 2013.

The matter was apparently shelved due to the “many controversies raised” at the meeting.

“This was unfortunate. Celebrities always attract controversy; the government should not have taken note of the controversies.

Konark being an emotive issue for the country, the government should have examined the social, financial and technical aspects in detail before accepting or rejecting the proposal,” Dey writes.

An organisation named Kalinga Heritage Preservation Trust (KHPT), of which Dey is a member, has stated that one of its “pronounced objectives was to create a Sun Temple in the architectural and spiritual tradition of Konark, where no human being would be barred from entry on grounds of religion, caste, colour or nationality”. According to Dey, ‘‘the project involves reviving the dying stone craft as well as spiritual research and tourism promotion.”

The trust explained their thoughts to civil society in two well-attended meetings to assess public reaction.

The proposal has now been sent to the state government,” he writes.

The Aga Khan Trust recently financed the complete renovation of Humayun’s tomb in Delhi.

In Italy, Tod’s, the luxury shoe retailers, are spending 25 million euros for the restoration of the famous Colosseum.

Fendi, a fashion house, is doling out three million euros for restoring Rome’s Trevi fountain and a diesel retailer is spending five million euros for restoring the Rialto bridge in Venice, the author writes and rues: “This trend is yet to catch up with the business tycoons in India.”

If Gujarat’s Swaminarayan sect could create Akshardham in Delhi, “why can’t the Odia community re-create Konark, their greatest architectural achievement, without waiting for government funds? The only possible answer is that the community has not yet broken loose from centuries of decadence.

Playwright Prativa Roy speaks through her character, Vishnu Mahasana, in ‘Silapadma’ (Stone Lotus): ‘Konark is vanishing in the cruel grip of nature; who will save it? Who will create a new Konark?’,” Dey writes.

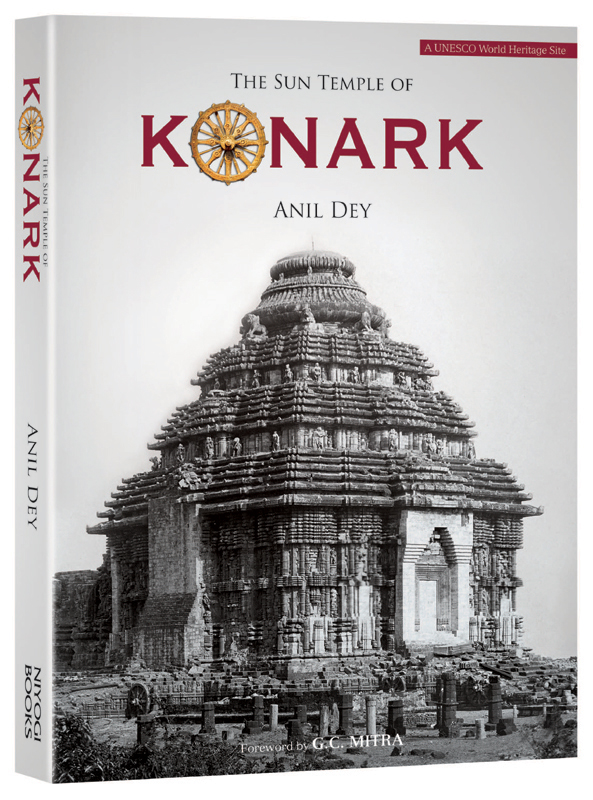

The book is the result of Dey’s extensive research into not only the history and legends related to the temple but also the legends about the temple.

An engineer and architect by profession, the author examines these two aspects of the temple in great detail.

He questions several of the established theories on the temple’s construction in its various stages and puts forward his own theories with reasonable conviction.

He takes great pains to go into as much detail as possible on each and every portion, monument and sculpture of the temple.

With 415 images and 21 detailed architectural drawings, the book is a treasure trove for any admirer or student of Konark, or a researcher of art, history and architecture.

Oman Observer is now on the WhatsApp channel. Click here