Funmi Ilori once had a dream about creating the biggest library in Africa. Now she drives vans packed with books to poor areas of Lagos to help children discover a love of reading. “Readers are what?” she asks about 15 youngsters, sitting on little plastic stools in a classroom in a small converted lorry.

“Leaders!” they shout back in unison.

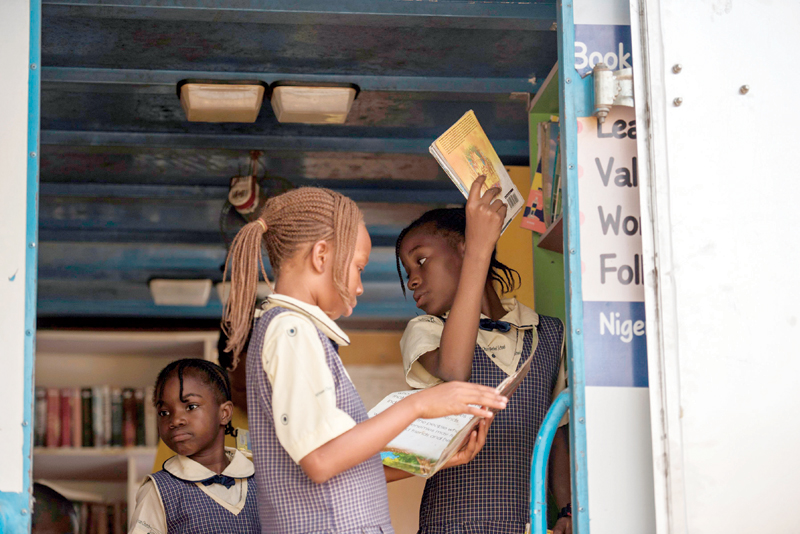

One of Ilori’s iRead Mobile Library vans recently stopped at the Bethel primary school in the working class district of Ifako, in the heart of megacity Lagos.

Inside the school compound, slides and seesaws rust in the humid air.

The head teacher, Ruth Aderibigbe, said her 200 or so pupils only have textbooks at their disposal.

“Books cost a lot of money,” she said.

When iRead turned up at the school two years ago with its wide selection of books, from toddlers’ colouring books to children’s novels, plus a few for adults, she welcomed it in with open arms.

“The children involved in the programme now speak and spell better in English,” she said.

Inside the van, a young boy aged about 10 held a copy of “Half of a Yellow Sun”, the international bestseller by the Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

The book has clearly been well-read: its spine barely held the pages.

Adichie last week became embroiled in controversy after a French journalist asked her during a visit to Paris whether there were any bookshops in Nigeria.

“I think it reflects very poorly on French people that you have to ask me that question,” she responded, going on to rue what she said was France’s racist and colonial view of Africa.

Ilori is aware of the row and understands why the question would offend.

But she sees a wider problem and has dedicated herself to trying to resolve it.

“Public libraries are functional in Nigeria, well, at least in Lagos.

But not many people maximise the use of them,” she said.

“We need to catch new readers from a young age.

In rural communities, there are children that have never held a book.

“I advocate for community libraries everywhere.

Just as churches are springing up, libraries should be springing up.”

Ilori is a former primary schoolteacher who began a book-lending business in 2003.

“Books in a basket. I was going door-to-door,” she recalled. Books could be borrowed for just a few hundred naira (a couple of dollars) but her experience led her to realise that few adults in Nigeria’s bustling economic hub had the luxury of having time to read.

Ten years after starting the “books in a basket” scheme, she came up with the mobile library idea and applied for funding from a Nigerian government development initiative.

The pitch was successful and landed her 10 million naira, which, with the exchange rate at the time, was the equivalent of about $60,000.

With it, she bought a lorry and a small minibus.

Now, thanks to the grant and sponsors, she has been able to take on 13 employees, buy 1,900 books and four vans.

She visits four to six schools every day, organising reading workshops on evenings and at weekends for out-of-schoolchildren in slum areas with the help of volunteers.

The vans function like real libraries: children choose a book that they read at home, bring it back the following week and write a compulsory “review” on what it’s about.

Sade chooses her favourite adventure story, even though she already knows it off by heart.

“Reading is my hobby.

Books give me ideas and they help me know better,” she says.

Adinga plumps for “Bioenergy Insight”, a magazine on renewable energy that he found on the shelves.

“Are you sure you’re going to read that?” asks one of the volunteers, amused.

The young boy pulls a face and puts back the magazine, eventually choosing a comic book.

Afterwards, the schoolchildren, dressed in white and green uniforms with a bow tie for the boys, proudly troop back into class.

Tucked under their arms are books such as “Toy Story” or “Goldilocks and the Three Bears”.Ilori looks and says there’s something missing.”We need more African children’s books now,” she says. As Adichie said in an interview published in The Atlantic in February 2017, the books she read as a little girl “and I think this is true for many other young children in countries that were formerly colonised, didn’t reflect my reality”. — AFP

Sophie BOUILLON

Oman Observer is now on the WhatsApp channel. Click here