Maggie Jeans OBE

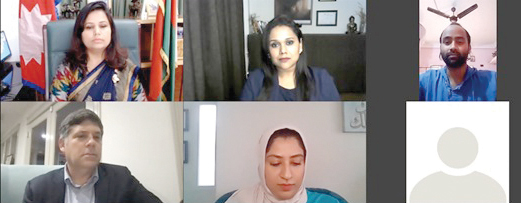

The Embassy of Nepal celebrated the life of the late Omani poet, author and traveller, Mohammed Ahmed al Harthy, via an international webinar with participants from different time-zones at which a website paying tribute to his work was launched, recently.

During his literary career, Al Harthy published several works — My Life is a Poem I wished I Wrote, Eyes All Day, Every Night and Morning, Further than Zanzibar and A Return to Writing by Pencil, as well as two books of travel literature and a novel entitled Revision of the Manuscript. A book about his travels in Nepal, Kathmandu’s Ocean has recently been published in Arabic posthumously and is now being translated into English by Dr Ethan Chorin.

The event was attended by several members of his family, including his sister Azhar al Harthy, Director of the Qurum Cultural Club, and his daughter, Ibtehal al Harthy, who is also a writer and illustrator. Dr Jokha al Harthy, academic and author of 10 books who recently won the Man-Booker International Prize for her novel, Celestial Bodies, was also a participant.

Nepalese Ambassador to Oman, Sarmila Parajuli Dhakal, commented, “We are delighted to host this event and to be able to acknowledge the late Mohammed al Harthy’s contribution towards Nepali literature and tourism though his travelogue. Oman and Nepal share many things in common and they are also two of the most beautiful countries in the world.”

Al Harthy was clearly an inspirational adventurer as illustrated by the following short extract from his book entitled Jogging into the Abyss.

I achieved my dream of free flight on the afternoon of 9th October, 2013.

The paraglider was equipped with two lightweight seats: One for the pilot and one for the passenger.

Damu, the pilot, sat in his seat and fastened his safety belt.

I had to stand in front of him as my backside was attached to the front of his seat.

His assistants unfolded the parachute behind us, as he explained to me that I had to jog in front of him up to the very edge of the mountain, with my seat fastened upright to my rear. “That seat will get more comfortable once we recover from running off the cliff,” he said with a straight face.

“Now,” Damu said, “the weight of our bodies fulfils a dual function. It helps fill the parachute with air and it fights our fall onto the abyss.

“But don’t be afraid, Mohammed, because there will be five seconds of panic, then you will feel that we are rising together towards the sky instead of falling into the abyss.”

I ran in front of Damu, but only after he had assured me multiple times that the various cords were fastened securely.

Damu gave signal that all was ready for takeoff.

The distance of the jog towards the abyss wasn’t more than 10 metres, and I ran towards it. And that was the only role asked of me because it is the pilot’s job to follow the steps of the person taking off until the takeoff is completed safely.

I did what was asked of me. Damu taught me a trick, to close my eyes at the moment of takeoff so I wouldn’t be overwhelmed by the cliff. But I didn’t close my eyes, because I wanted to enjoy the experience in full, without missing a single moment. Just as my feet arrived at the precipice, we fell for a few seconds towards the abyss. But I barely felt it, for as soon as I was conscious of the drop, the parachute performed its defensive role, protecting us from the fall.

After takeoff, Damu tried to alert me to take my flying position, seated on the platform attached to my behind with a safety belt. But I was oblivious to his order, and continued standing, gesticulating in the air.

I still believed that I was running on the edge of the mountain whose touch had already escaped us. We were airborne. Damu was behind me, and once he sat down himself he was positioned above me.

“Relax!”, he said, — “and sit on your seat! And keep your legs pointed down!”

I did what I was told and let out an inadvertent sigh of relief. Sitting was a very simple thing to do, but still I was afraid to do it, lest I fall.

I became aware that I had just realised the dream.

When I looked to the other side of the glider, I saw the panoramic beauty of the city of Pokhara and Phewa Lake in all their glory and also the surrounding snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas.

I asked Damu about our height and he looked at his watch, which had an altimeter built into it.

“We are currently at a height of 2,176 metres above sea level, I will try to raise us 100 metres higher, then we will begin the gradual descent. Agreed?”

“You’re the pilot, and I will do what you tell me,” I said.

“I can start the manoeuvres at the half way point — that will induce the parachute to tumble head over heels multiple times, a bit like you see fighter planes do in films. A lot of my clients can’t stand it, because the fear paralyses them. Are you sure you’re ready for the full impact of the experience?,” Damu asked me.

I told him I was, most definitely.

“You will see Pokhara and its lake spinning around you while we do these manoeuvres. If you are uncomfortable and can’t stand the repetition or the forces on you, tell me, because people who aren’t used to it can experience vertigo and vomiting.”

Suddenly my fear disappeared, and I felt an immense tranquillity.

“I’m ready,” I said.

Damu tugged on the magic cords expertly, and off we went.

“Prepare yourself,” were the last words I heard before the sky lowered in front of my eyes and the lake and the neighbouring parts of Pokhara flipped above, wrapped in a ball of dizzying speed. We flipped over 90 degrees to the level of the horizon, until we were upside-down, and then had to complete the 360 degree rotation, only to start again — thrilling moments.

At first I had felt vertigo, but not nausea. After a few somersaults, pushing the limits of the thrills that free flight can produce, I felt like throwing up. We did not approach land, the land approached us the moment Damu put us into the roll, directing us to the grassy landing patch. Damu reminded me of the need to move my feet forward for landing, until the parachute released the air that kept it aloft.

I did what Damu asked me to do, to the best of my ability, and lo and behold, we landed safely.

Mohammed al Harthy’s works can be seen on: www.mohammedalharthi.com

Oman Observer is now on the WhatsApp channel. Click here